Arkansas’s 2023 legislative session was marked by a series of culture wars. From being argued on social media to being debated in committees, multiple bills were based on outright discrimination and the latest far-right talking points. Many of the more egregious examples were watered down or weeded out instead of being made the laws of the land. However, it’s naive to assume that the only threats to our democracy are held in the bills that became law.

Even if extreme bills don’t pass, there are still consequences of having them brought into the lawmaking process in the first place.

Bad bills negatively affect Arkansans whether they pass or not.

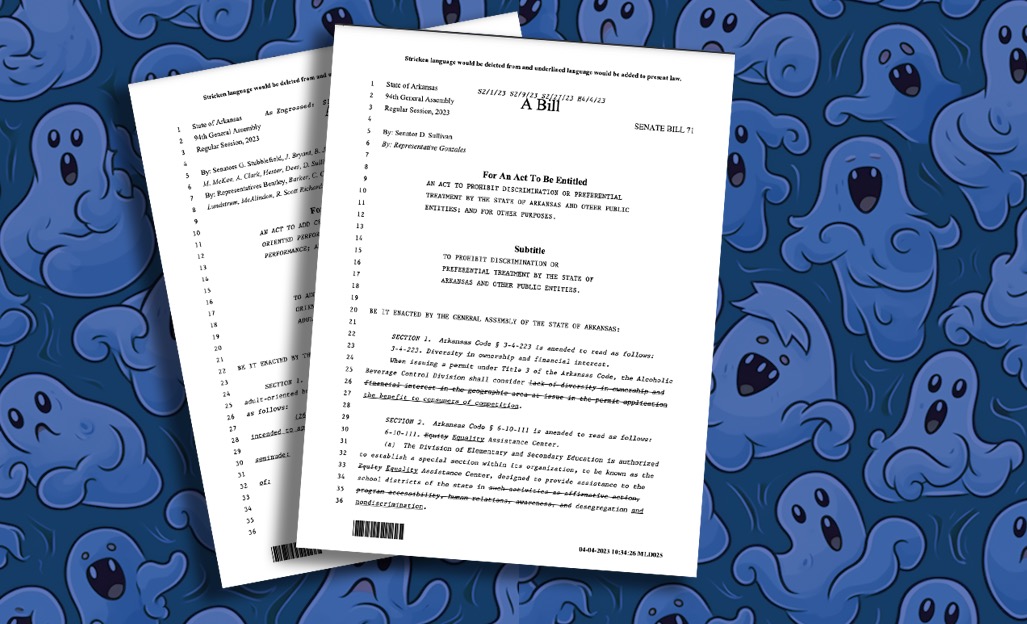

This year Senator Dan Sullivan failed to pass SB 71, which would have ended affirmative action in the state of Arkansas. Sullivan’s repeated claim about this bill was that it would “end state-sponsored discrimination” and make “affirmative action available to everyone, not just a select group.” His brazen campaign promoting the bill included a meeting with the Legislative Black Caucus in which he implied the members of the caucus should cosponsor the bill. Sullivan also pushed a committee vote on an amended version of the bill that had not been made available to the public. After all his efforts, the bill failed to pass the House and was recommended for further study.

Last month the Arkansas Minority Health Commission discontinued its Minority Health Workforce Diversity Scholarship to settle a lawsuit from an out-of-state organization claiming the scholarship was unconstitutional. The commission has a stated mission to “assure all minority Arkansans equitable access to preventive health care and to seek ways to promote health and prevent diseases and conditions that are prevalent among minority populations.” The scholarship did exactly that, as it increased access to higher education for women and people of color. More minorities and women in health care means the same populations are likely to seek care to prevent negative health outcomes.

This lawsuit settlement came on the heels of several months of effort by a sitting State Senator to overturn affirmative action. In the process of arguing for his bill, he successfully normalized his extreme position that historically marginalized populations should not have their own avenues to access the healthcare field (or any other field where they are historically underrepresented).

The bill did not pass, but because it became more normal to disparage a long-standing initiative for equity, damage was done.

We’ve seen a similar outcome in regards to Senator Gary Stubblefield and Representative Mary Bentley’s bill, SB 43. The bill was first introduced as an explicitly anti-drag legislation, specifying in its subtitle that drag performances would be classified as “adult-oriented.” The bill was amended to avoid discrimination lawsuits, with its final iteration refraining from explicit mentions of drag altogether. This change was celebrated among LGBTQ+ advocates, and the bill passed as amended.

Even with a new, gutted version of SB 43 being passed into law, the Walton Arts Center chose to forego hosting drag shows in the youth zone at this year’s Northwest Arkansas Pride weekend. There is no explicitly anti-drag law in the Arkansas code. The risk of being in violation on a technicality—or more likely, drawing negative attention from anti-LGBTQ+ protests and bad actors—is too high. The Walton Arts Center issued a statement after public pushback, local protests, and several board members resigning due to the decision.

The legislation that comes through our General Assembly affects the norms and culture of our society even when the legislation doesn’t pass. This is a testament to the power and influence of our elected officials. Their intended outcome of the most extreme bills is to shape society based on their ideologies. Lawmakers can achieve that influence by using the legislative process to normalize their own brand of extremism.