What kind of difference does a single word make in the law? If you’re a law restricting abortion access, quite a lot.

Today, we’ve got a deep dive for you on the consequences of one word choice in Arkansas’ patchwork of abortion laws. What, after all, is the difference between “life of the mother” and “health of the mother” exceptions?

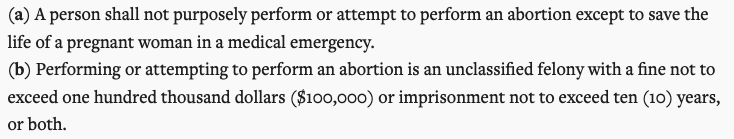

The Text of Current Arkansas Law and Its Inability to Protect Women

There are a lot of abortion statutes in the Arkansas Code. Some of them even conflict with each other; before Roe fell, the legislature did everything it could to make abortion harder to access, but after Roe fell, they were too lazy to go back and clean up the Code by repealing or amending these old laws (for example, §20-16-2004 is still on the books, prohibiting abortion after 18 weeks’ gestation).

Today, §5-61-304 and §5-61-404 control abortion in Arkansas; the text for §5-61-304 is above. As most Arkansans likely know, these sections create a total ban. There are no exceptions for rape or incest and no exceptions for fatal fetal abnormalities, despite efforts by state representative Nicole Clowney to get these commonsense and compassionate exceptions on the books. The only exception is to “save the life of a pregnant woman in a medical emergency,” where a medical emergency is defined as a life-threatening physical condition, whether or not it’s caused by the pregnancy.

Two important notes before we dive in:

- In another section the law specifically excludes ectopic pregnancies; they don’t count as an abortion. This is an obvious rhetorical trick by the legislature — the treatment for an ectopic pregnancy is functionally an abortion; a fertilized fetus is removed from a woman’s body. Sounds like an abortion.

- If the fetus has been miscarried, removing the fetus doesn’t count as an abortion under the law. Again, see this for what it is: a rhetorical sleight of hand. Depending on when the miscarriage happens, the removal of the dead fetus is often the same or similar procedure as an abortion; the point is that the medical care in the situation is designed to protect a woman’s health.

If you’re opposed to abortion, you might think this covers it! Of course, women shouldn’t die to give birth, but why else would an abortion be necessary?

But there’s a problem here: preserving just the “life” of a mother leaves a lot of things that can go wrong before doctors might be in the clear to perform an abortion. A lot of medical damage — often permanent — might happen before someone’s “life” is in danger.

Sometimes doctors don’t realize a woman’s life is in danger in time; they’re stuck waiting for a magical line that’s so fuzzy it’s barely visible while a woman is desperate for medical care. We go into some more detail about that in our piece on maternal healthcare. It’s hard to overstate how quickly things can change in a “medical emergency” as defined by the Arkansas Legislature. One moment, a woman might be in pain, but not at risk of dying. In the next, she could have mere minutes until the damage is irreversible or fatal, but doctors’ hands would still be tied if they are unsure whether the woman’s condition is “life-threatening.”

Here’s the point: preserving the “life” of a woman does not equate to preserving her “health.”

Let’s discuss one of the more heartbreaking examples of this in recent history.

What’s Wrong With Basic “Life of the Mother” Exceptions?

In 2018, Ireland held a referendum and overwhelmingly passed something very similar to the amendment proposed by Arkansans for Limited Government. It’s commonly understood that the six-year push in Ireland to enshrine the right to make these private healthcare decisions was, in large part, sparked by the death of Savita Halappanavar, an Irish-Indian dentist who died when her pregnancy went septic.

On October 21, 2012, Halappanavar, at 17 weeks’ gestation, went to the hospital complaining of back pain. She was discharged without a diagnosis, but came back to the hospital that same day complaining of more pain and uncomfortable sensations. She was admitted and doctors determined that a miscarriage was unavoidable, but she was denied an abortion because, at the time, a fetal heartbeat was detected. A week later, on October 28, 2012, Halappanavar died of sepsis at the age of 31. A governmental inquiry found that a number of things went drastically wrong in her treatment, but one thing was clear: an abortion would have saved her life. The fetus would never live, no matter what doctors did, but because doctors’ hands were tied, two lives were lost.

Relevant to Arkansas’s current abortion law is this fact: Ireland had an exception for the “life of the mother,” but it didn’t save Savita Halappanavar’s life. This is the risk with only “life” exceptions — a patient’s medical condition can deteriorate incredibly quickly, and by the time a legal consultant signs off on an abortion for a dying woman, it’s all too often too late.

Why “Health of the Mother” Exceptions Make a Huge Difference

There’s a big difference between someone being alive and someone being healthy. Let’s move over to Texas. Twenty-two women have signed onto a lawsuit alleging that the state’s abortion laws have caused them grievous harm by forcing them to carry dangerous pregnancies. In some cases, the state essentially forced women to carry dangerous pregnancies that might have long-term negative consequences to their health. All the pregnancies were dearly wanted, but because the women’s lives weren’t yet in danger, there was nothing doctors could do except recommend their patients go out of state.

Adding “health of the mother” exceptions lets doctors protect women before their lives are in danger. Think of a “life only” exception like being in freefall and being told you can only have a parachute at the very last second. There’s not a lot of time to make a decision or to deal with any complexity or nuance. A “health of the mother” exception is like being given a parachute before you jump out of the plane.

These are essential exceptions to abortion bans. They protect women, families, and doctors. We can – and should! – discuss what “health” means in this context, but it cannot be that a woman must put her entire life at risk just to have a child. It cannot be that we force families to grieve over and over again for a child that will never live outside its mother’s womb because a doctor can’t legally let the family choose their own path through grief.

These exceptions are compassionate and commonsense. That’s what Arkansans value, not draconian and dangerous policy.